F.H.Gidding's letter of Feb 5,1890 to J.B.Clark,Bryn Mawr.

F. H. Giddings' letter of Feb 5, 1890 to J. B. Clark, Bryn

Mawr.

Dear Friend:

We understand each other at

last I think. There has been a real

difference of thought. Your arithme-

tic is as clear as sunlight. The

only question is whether the prob-

lem is simple or complex. Your

admission that you do not ac-

count for interest by the time ele-

ment alone quashes the case so

far as my argument against your

position is concerned. My con-

tention in the Quarterly article is

simply that if anybody undertakes

to account for interest solely by

the difference between present and

future values of goods "of like kind

and number," as Böhm-Bawerk puts

it, he must face the fact of double

interest. The question then becomes

whether I have misunderstood

Böhm-Bawerk's theory of the rela-

tion of capital to production: have

I been wrong in supposing that

he undertakes to account for in-

terest apart from the productivity

of capital? I have understood

precisely as you understand, that

he admits the increase of goods

through capitalistic production, though

attributing the increase to the effort

of man rather than to any potency

of capital. I agree also with you

that this is, so far as it affects

the question of interest, merely a

verbal distinction. But the seri-

ous point in B. B's theory, as I under-

stand him, is a different thing from

this altogether. I understand him

to deny that the production of

additional goods in the capital-

istic process is also a produc-

tion of additional value. "Great

product is antagonistic to great

value," is the dictum on which

he rings the changes. If there is

no production of new value when

the 100 bushels of wheat become

the 110, then interest must be ac-

counted for wholly by the time ele-

ment, and this, I have supposed

was B. B.'s conclusion. And I can

hardly think that I have been mista-

ken, in as much as Dr. Wieser and

Mr. Bonar have both evidently under-

stood him in the same way, not

to mention Patten, to whom I sub-

mitted my statement of B. B.' s position

and who said that this was his under-

standing of it. If you will turn

to Der Natürliche Werth' pp. 133-139

you will see that Wieser enters

into a long argument against

what he understand to be B. B.'s

doctrine that the "more product" of

capitalistic production is not

"more value." Glance then at Mr.

Bonar's reply to me and at his re-

view of Böhm- Bawerk, and I think

you will be satisfied that he also

understand B. B. to deny the "more

value."

On the basis of this understanding

I have supposed that all who ac-

cept B. B 's conclusions, as I thought

you did, regarded interest as the

difference between present and

future values of the same goods

apart from the increase of

product in production. What

other possible meaning can

you attach to Bonar' s sentences;

(Quarterly, October, 1889, page 81 .)

"To writers who agree that inter-

est is a question not of produc-

tion, but of distribution, it could

never appear right to describe

interest as 'a unique stream of

wealth drawn by means of capi-

tal from the bounty of nature'. To

them it is a problem not of sur-

plus product but of surplus value."

Now apply these notions to

our illustration and you will

see instantly just where you

and I have differed.

You say (in effect): A's 100

units of deferred enjoyment are

today worth 91 and would exchange

at a discount with B's 100 units of

present enjoyment but for the

fact of prospective increase by

production. But taking that pros-

pective increase into account

A's 100 units of deferred enjoy-

ment become equal today to

B's 100 units of present enjoy-

ment. Capital goods, therefore,

because of this productive in-

crement, which cancels the dis-

counting of futures, exchange on

an equality with present con-

sumable goods.

Is this a fair statement of

your position? If so turn to

what I think would be a fair

statement of Böhm-Bawerk's, Bonar's

and Patten's:

A's 100 units of deferred en-

joyment are worth toady 91. These

100 units are (1) commodity or

goods, (2) value. In the process of

capitalistic production they

will become 110 units of com-

modity, but never more than

100 units of value. Therefore

there is no prospective increase

of value to offset the discounting

of futurity. Therefore, further, 100

bushels of wheat to be set aside

as capital are not equal in

value today to 100 bushels to be

devoted to immediate consump-

tion, although the capital wheat

will presently become 110 bush-

els. Therefore, finally, in the div-

ision A will not accept 100

bushels of seed wheat as equiva-

lent to B's 100 bushels of con-

sumable wheat, but will in-

sist on taking 105 bushels leav-

ing to B 95 bushels, and this

additional share that A takes is

interest.

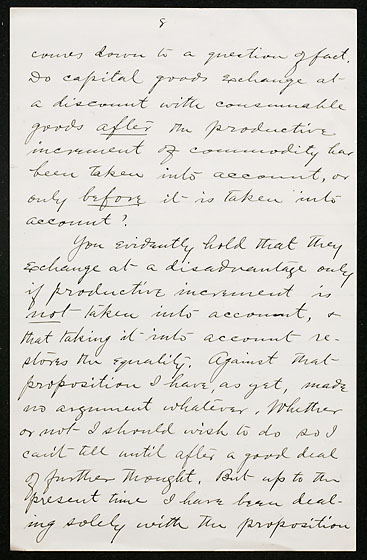

The whole thing thus

comes down to a question of fact.

Do capital goods exchange at

a discount with consumable

goods after the productive

increment of commodity has

been taken into account, or

only before it is taken into

account?

You evidently hold that they

exchange at a disadvantage only

if productive increment is

not taken into account, and

that taking it into account re-

stores the equality. Against that

proposition I have, as yet, made

no argument whatever. Whether

or not I should wish to do so I

can't tell until after a good deal

of further thought. But up to the

present time I have been deal-

ing solely with the proposition

that after increment of com-

modity has been taken into con-

sideration capital goods still

exchange at a disadvantage with

consumables: in other words, with

the proposition that the capital-

ist takes an extra share in dis-

tribution on the assumption

that his waiting is not otherwise

recompensed. I have contended

that his waiting is otherwise

recompensed, by productive

increment, (and you, it now

appears think so too) and there-

fore that, having taken an extra

share in distribution on this

assumption, and the assumption

itself bring false, the capitalist

gets double interest unless one

rate of interest is cancelled

by a cost of production.

If with this explanation in

hand you will turn again to my

article, I think every point in

it will become perfectly clear

to you. Glance over again with

this explanation in mind, the

matter from the top of p. 197 to the

top of p. 203.

Now if you can make

good your proposition that capi-

tal goods do not exchange at a

disadvantage with consumable

goods after productive incre-

ment has been taken into account,

I shall have to adjust my theory

of cost of production of capital

to a wholly new set of theoretical

considerations. I do not for a

moment think that the demonstra-

tion of your proposition would

throw the cost of production of

capital out of the problem of inter-

est. It would simply change its re-

lations to several other things. Not

to go into this fresh line of argument

just now, I will merely

call attention to the fact that, when

you admit an increase of goods

by the capitalistic process you

are brought instantly face to

face with the problem why do

not capital goods so multiply

in supply that their marginal

utility as capital becomes zero?

In other words, don't you find

yourself brought square up against

the conditions that lead Böhm-Ba-

werk to deny that the "more prod-

uct" of capitalistic production

is also "more value." My way

of saving a way out for your

theory of interest would be by

invoking the cost of production

of capital goods. If it shall

appear that that way is n.g.

I don't see why you and

Böhm-Bawerk aren't both

of you between the devil and

the deep sea. In such a

dilemma I should credit you

with the courage of conviction

to plunge into the depths - but

Böhm-Bawerk - he certainly

would be devoured!

Sincerely Yours,

F. H. Giddings

![]()